- Home

- Jill A. Davis

Ask Again Later Page 2

Ask Again Later Read online

Page 2

We all regress when we’re scared. Why shouldn’t he? That was his upside to our crisis. During my mother’s treatments he started a maniacal dating spree. It has always been his favorite coping mechanism. A similar spree ended my parents’ marriage twenty-five years ago.

A few weeks ago he was dating a woman who’d graduated from school three years ahead of me and made her living selling makeup out of a pink suitcase. When she was in the waiting room, I was curious, so I asked to hear her sales pitch and ended up buying some moderately priced lip gloss from her out of guilt. We chatted for twenty minutes. There was nothing overtly objectionable about her, and at the same time there was nothing obviously wonderful either. Yet my father landed himself here.

There are moments when I believe I could travel down this path of thought and never return. But the ringing phone snatches me back—a literal tether to reality.

Breakdown

IF I WERE LOOKING at a map of my life, this is the point of the journey at which I’d have to ask myself: How the hell did I end up here? Answering phones? Reunited with my father? Trying to micromanage office pizza parties? This was not the future I envisioned. These are not the dreams I hatched while sleeping on rainbow sheets in my single bed. It has nothing to do with lack of ambition. Far from it. I graduated from college and went directly to law school without taking a summer break. Two days after graduating from law school I started logging seventy-hour workweeks at the respected firm of Schroeder, Sotos, Willett, and Ritchie.

I kept myself buried in work. Obsessed with it. Glancing up every so often to see there were other important things in the world. Things I had no time for until my mother found a lump. A small lump that changed everything.

All of the things in my life that worked suddenly seemed broken. So I abandoned my former life. Truth be told? It was an emergency escape hatch that released me from a job that had kidnapped my personal life, and got me out of a relationship I was too afraid to engage in.

When pressed to tell people how I got myself into my current nepotism-gone-bad situation, I like to describe it as a mini-breakdown. The prefix makes all the difference. It makes it sound more like a vacation than a condition best treated with medication and art therapy.

I can pinpoint the morning that things changed. As usual, I was on a self-improvement mission from the time the alarm clock sounded. Each morning I woke with the same promise to myself. I would work less and live more. Every day I broke that promise and ate takeout for dinner at my desk and pretended not to be in love with Sam. I was looking for ways to enhance my life without having to change anything significant.

My Shrink

PAUL’S OFFICE IS COZY, and by cozy I mean there is a white wicker daybed in lieu of a couch. The first time I came to see him there were pastel-colored butterfly sheets on the daybed, and I almost didn’t come back because of that single detail. I tortured myself with what it could all mean—his choice in sheets. Are we all meant to soar in this world? To see things from the vantage point of a metamorphosing insect? Or were they just sheets that happened to fit the daybed? As soon as he gets an actual couch, I’ll be lying on it. Until then, I’ll sit across from him in the black, foam-stuffed pleather club chair.

“So, what’s happening in your internal life?” Paul asks.

“Who’s got time for an internal life?” I say.

“Not a hell of a lot happening in your conscious life,” Paul says.

“Ouch,” I say.

“Well, not anything you’re willing to talk about,” Paul says.

I steal a glance at him. He needs a haircut. Like all shrinks, he wants me to talk about my mother.

“Whatever happened to that guy? The one who had the appointment after me?” I ask.

“Why do you ask?” Paul says.

“I think I miss him,” I say. I can’t handle separations that aren’t accompanied by lots of advance notice.

“I see,” Paul says.

“You cured him, and I’m not sure I’ll be able to forgive you,” I say.

Silence.

“Because you miss him? Or because I ‘cured’ him and not you?” Paul asks.

I look him over for thirty seconds or so.

“You’re good! And feisty, too,” I say. “But either way you’re in the wrong, and I’m not forgiving you.”

He laughs. His eyes go from happy to sad on a dime. A hair trigger. He’s mastered empathy.

“I liked that ratty backpack he carried. Even though he was too old to carry a backpack—in my opinion. And then, just before he stopped seeing you, he switched to a leather briefcase. No scuffs. Brand new. I should have taken that as a sign,” I say.

“Sign of what?” Paul asks.

“That he was ready to move on. That he’d grown up or something,” I say.

“It’s about being a grown-up?” Paul asks.

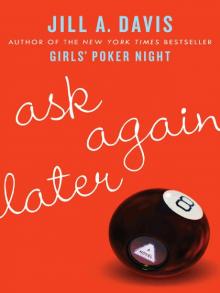

“Ask again later,” I say. It’s my favorite non-answer.

Then I shrug. I wait. I have no idea what “it’s” about. But I return week after week in hopes of finding out. One day I’ll walk in, and my number will be called, and he’ll hand me my fortune, which will tell me everything. I need only to keep showing up. You can’t win if you don’t play.

I access some of my conversation filler, something along the lines of: Isn’t it time to stop screwing around and grow up?

“There’s no such thing as ‘grown-up,’” Paul says.

“That’s encouraging,” I say.

“If you really think about it—it is encouraging,” Paul says.

Silence. I stare at the trees in the park. There is ice on the branches. I can see the skeletons of old bird nests. Every so often the branches catch the wind, like a kite. A visual lullaby. Some ice falls. Then I imagine the cost of pruning those trees. That always breaks the spell. Must be absolutely astronomical.

Peace on Earth and The New Yorker

I LEAVE HIS OFFICE and sit in his waiting room. I’m not quite ready to go home—to mine or my mother’s. There is a white noise machine. Four mismatched chairs, one couch, one coffee table. A dysfunctional family of furniture.

On the wall is a small hand-made sign that says: “Please, turn off cell phones in waiting room.” I cross out the comma after “Please.” It’s my way of giving back. This is just one example of my quiet helpfulness.

And suddenly I’m struck with an understanding of why people go to church. It’s a lot like this waiting room. I don’t associate it with anything other than dog-eared copies of The New Yorker—and quiet waiting. It’s a good kind of waiting, because there is no line and the appointment always starts on time. The outside world doesn’t knock on the door here. It’s genuinely peaceful. Peace on Earth.

My mind travels back to the morning that changed things.

Tin-Foil Swan

I AM IN MY NEW kitchen thinking about myself. I am envying my own life up to this point. I am that person. The one who buys the gigantic, shiny coffee-espressolatte-cappuccino machine in hopes that it will replace or enhance my internal life.

It’s not your father’s Mr. Coffee…no sir! It’s the kind of sleek stainless steel “system” that takes up several cubic feet of the pricey Manhattan real estate that is my kitchen counter. Could be worse, I could be a fan of mug caddies. Those spindly little racks that display mugs for people who can’t manage the extra effort it takes to put the mugs inside a cabinet. You never want to be too far from your mugs…don’t want to be separated by prefab cabinetry. Or even a hardwood, such as maple.

When the coffee fad is over—though let’s face it, I hope it’s not a fad but an accepted addiction that will never be socially demonized—this “system” will not be obsolete. It’s also a hot-water-on-demand machine! Good strategizing, if you ask me. It’s too heavy to move, so at least it’s also capable of emitting scalding hot water.

I bought it so I’d stay home more. I bought it instead of getting a pet. It’s the closest thing to a living being without actually breathing or needing health insurance.

It speaks to me in concise phrases, without prolonged sentences that are weighed down with “ya know” and “at the end of the day” and “basically” and “um” and “like”—which I really appreciate. “Fill water tank. Fill coffee beans.” It’s direct and to the point. It’s one of the most uncomplicated and rewarding relationships I enjoy.

In fact, it was so uncomplicated that I was tempted to complicate it. I wondered, in the wee hours, after my new baby had been unpacked and readied for coffee making in the A.M.—whether the other appliances would be territorial? Jealous? For such a new appliance it certainly was receiving an undeserved amount of space. Of course, the refrigerator wouldn’t be able to complain about that! Although the microwave would have a legitimate gripe. Even I recognize that with all of these imaginings, I’m going well out of my way to avoid my internal life. But recognizing it doesn’t negate it!

One way I could give my internal life a leg up is by having only one newspaper delivered. But which one would it be? Do I want the Wall Street Journal more than I want Page Six of the Post? And on the day I have the time to read the whole Sunday Times, will that be the first day I don’t have home delivery of the Gray Lady? The price of abundance, I’m learning, is constant indecision.

I’m about to enjoy some frothy milk and coffee, read Page Six and at least the front page of the Times, when the phone rings.

I look at the coffee machine, in hopes that it might indicate whether or not I should answer the phone. A modern Magic 8-Ball. It doesn’t reassure me, so I don’t answer. I wait, try to stick to the plan—read my paper, drink my coffee, breathe. Then I play the message.

“Tonight,” Sam says, “if we’re out of there at a reasonable hour, I think we should do…something.” His voice is sleepy and subdued enough for me to wonder if he’s sleep-dialing—acting on some fantasy—and won’t remember he’s called.

“I’ve been up since four o’clock waiting for it to be almost six o’clock so I could call you. I just miss you, and I’m really fucking lonely,” Sam says. “Lately, when I think about you, and lately it seems like I can’t stop—of course it doesn’t help that I see you every day—I don’t even think about anything great. I keep thinking about that week we were working together in L.A.

“That night I knew you were awake in your room and you wouldn’t open the door. And outside of your door I left some steak that the guy at the restaurant wrestled into the shape of a swan. I thought you’d think it was really funny and come looking for me. Every time I think of that I feel like such a jackass. I gave you leftover meat in a fucking tin-foil swan. Why did I think you’d respond to that?”

It’s the call I’d been waiting for. What is the worst thing that could have happened if I’d answered the phone? Or opened that door? I would have to live my life.

He was right, of course. I was in my hotel room, worrying what hypothetical and amazing thing might happen next, yet afraid to find out. I waited twenty minutes before venturing into the hallway to see what Sam left. The swan. There’s only one person in the world who would try to seduce a woman with leftover New York strip—and I let him get away!

Sam has this funny way of seeming more real on the phone than he is in person. Not more real, but more himself. He feels safer the farther away he is. He’s like me, in this state of paralyzed limbo. It’s the dance of avoidance that happens when your wife leaves you and you meet a woman whose father walked out on her. You are locked in perfect step.

If it were going to happen, it would have already happened. (Admittedly, even while I’m thinking this, I’m hoping it’s not true. It’s too simplistic, and when you apply the statement to almost any situation, frankly, it doesn’t hold up. I mean, what does its not having happened yet have to do with preventing it from happening in the future? Nothing! Is it a predictor of things to come? Who knows! I don’t want the statement to be true, of course. It’s just true for now. That gets my hopes up, which just lets me down, so I need to stick with this thinking—you see.)

The Lump

I WANT TO LEAP through the phone and kiss Sam. I want to thank him for being honest about how he feels and the things he regrets. The phone rings again. I skip the small talk. The hellos. I just answer and speak:

“It’s not personal. It’s situational. I’d be all over you if I didn’t have to sit across from you at every meeting,” I say. “Let’s not forget the Christmas party. One kiss and I get called into HR and am asked to reread and sign the non-fraternization policy again—in front of a witness this time. I felt like I was twelve. My feeling is if I’m working seventy hours a week, and I have the energy to kiss anyone, including a coworker, my stamina should be applauded. I should get some kind of bonus for compartmentalizing my life so beautifully and to the firm’s advantage. Our timing has always been off, Sam.”

I never go out on a limb, but it feels breezy and wonderful out here; I’m weightless, unburdened! And at the same time it’s starting to seem…eerily silent.

“Hello?” I say.

I want Sam to reassure me. Tell me that we make our own timing. Everything will be okay.

“Well, kudos to you, honey,” my mom says. “That’s just good common sense. In my day, relations with a coworker were considered dirty, even cheap.”

Of course I don’t confess that “dirty” may well be the allure of it. And “cheap” only sweetens the pot.

“Relations?” I say.

“It’s none of my business,” my mother says. “I wish I’d slept around when I was young and had a different body and done all sorts of things I’d be ashamed of now, too. Who’s HR?”

“I’m not sleeping around,” I say. I knew no good could come from my answering the phone this early in the morning. Why had I second-guessed myself? Only people on a mission make calls at that hour. The kind of people who have been pacing their kitchen waiting for six-thirty to arrive. There’s no adequate preparation for that kind of ambush.

“Emily, you’re a grown woman; do as you please,” my mom says.

“I am doing as I please. Why are you calling so early? Is something wrong?” I ask.

“You’re going to have to call in sick today,” Mom says. “I really need you.”

The requests for me to call in sick happen regularly and usually mean someone bailed on lunch, or golf, or a spa day. She needs a seat-filler. The notion of paying in full for something she failed to cancel twenty-four hours in advance is one of her bigger beefs.

Someone will pay. Usually, it’s me. Even in high school it was an issue. I’d sleep through the alarm and she’d gleefully meet me in the kitchen at ten A.M., asking what “neat” thing we should do that day. I was tardy or absent from nursery school a record forty-seven times…and it was only a three-day-a week program. I was a very convenient breakfast companion for my mother.

“I need to go to work today. I could meet you for dinner, or stop by after work,” I say. “We’re almost finished with this project. I can even take a vacation when it’s over. Could we go to Florida?”

“I need someone with me now, right now,” Mom says. “I’m dying.”

“Dying? Come on, Mom. What is that can’t wait until seven o’clock tonight?” I say, getting annoyed.

“Cancer,” Mom says. “And I don’t want to be alone with it in my living room anymore.”

Impersonating Happiness

MY MOTHER HAS never been a reliable narrator of her own story. Once, she had a heart attack. It was the very best kind of heart attack a person can have. It was the kind that happens when a person self-diagnoses—actually misdiagnoses—her own panic attacks. She was immediately given a clean bill of health from a cardiologist. The second, third, and fourth opinions concurred with the first opinion. Out of habit and suspicion, she continued walking around holding her chest for several weeks, while swearing off red meat and chasing down her aspirin with Bordeaux.

My family communicates through extremes: comedy or silence or high drama. Speaking directly, or from the hear

t, is too “on the money.” It would eliminate all the anxiety of a surprise, of nuance. Nuance, it turns out, is very convenient. The perfect scapegoat. You don’t necessarily have to mean what you say. You can even pretend to be misunderstood. Humor impersonates happiness.

When my parents told me they were divorcing, they joked about it for weeks. My mother giggled about my father’s appearance, his lack of organization, and his inability to dress appropriately without someone’s laying out his wardrobe. He wouldn’t know how to find his way home, which was fine, since he wasn’t welcome to come home anyway.

My father laughed about how my mother would be afraid to leave the apartment without him. All dressed up and too afraid to go. She would have to live her life on the phone, he said. Which was fine since she never stopped talking.

Neither one of them was kidding, and neither one of them was funny. At least not on a topic so close to them or so new to them. Their marriage wasn’t—it turns out—a mistake. They were well suited for each other even if they couldn’t manage to be happy. They did fit, in that peculiar way that incomplete people sometimes do. They failed in different areas, and when they felt up to it, they picked up the slack and helped each other. Most of the time that worked.

My mother relied on my father’s total lack of social awareness to get herself out the door under the guise that she was helping him navigate the world. My father needed structure; he needed to be steered by my mother. He was her confidence, her most practical accessory.

The Davenport

I SAW HER two days ago. She didn’t look ill. She looked fantastic. Healthy. She looked like a woman who’s had her share of well-researched, age-minimizing treatments, including but not limited to a thoughtful, agonized-over surgical tweak here and there.

As I let myself into her apartment and take my key out of the lock, I call to her: “Mom.” I want to hear her voice before I walk in because I fear she may already be dead. I don’t want to discover her body in the worst scavenger hunt ever.

Ask Again Later

Ask Again Later