- Home

- Jill A. Davis

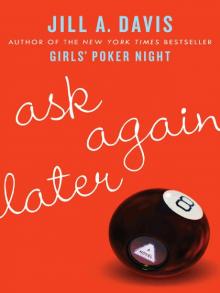

Ask Again Later Page 13

Ask Again Later Read online

Page 13

Pimp My Bowl

ON THE WAY to meet my father to share a cab to work, I pass Petland Discounts. It must be where Dad bought Happy. I walk inside. It smells of dog. Happy traded up in a big way. He’s the office darling.

I walk over to the fish equipment aisle. I select a net. Some water purifier. I’m about to go and pay when I see something Happy has to have. A treasure chest. The lid is propped open and a bounty of coins and jewels spill out. I buy some hot pink gravel and a floating thermometer and some live plants. Nothing’s too good for Happy.

I see a miniature scuba guy. It offends me. I instantly recognize it as something that would scare Happy—being trapped in a bowl with a small man dressed in latex.

An hour later, Happy’s home is transformed. It’s so nice I wouldn’t mind living in there.

I open the top drawer of my desk. I pull out a card. Mom’s oncologist Dr. Kealy gave me the name of his favorite mammogram guy. They never miss anything, he said. If I have time to decorate a fishbowl, I probably have time to get a mammogram. Besides, Happy needs me.

Colic

WHENEVER I CALL Marjorie, it’s a bad time. Big Malcolm is never home, and her baby nurse du jour has just quit, just stolen, or just broken something irreplaceable and needs to be fired.

“I’m a terrible mother,” Marjorie says with a certain amount of pride and resignation. “At least I can admit it!”

“Do you need some help?” I ask.

“Yes. I need help, then I need cameras to watch the help. Then I need help firing the help. The first baby nurse took my engagement ring,” Marjorie says.

“That’s horrible. Where was the ring?” I ask.

“Hidden. I wasn’t wearing it when I was pregnant because my hands were so swollen. So before I went to the hospital I put it inside of a sock, with some cash, and then put that inside of a rain boot in my closet. The money is gone, and so is the ring,” Marjorie says. “She was here a few days before Malcolm was born to get things organized. She must have ripped the place apart as soon as I went into labor.”

“What did the agency say?” I ask.

“Said I shouldn’t have left any valuables around the house,” Marjorie says.

“That’s helpful,” I say. “Why don’t I come over?”

Little Malcolm is crying in the background throughout the conversation.

“You really don’t want to. All this baby does is cry,” Marjorie says. “No wonder Big Malcolm never comes home. I wish I didn’t have to come home. I’m starving, and I can’t seem to find time to order food.”

“Just let me pick something up and come over; I promise I won’t stay long,” I say.

“Arrive at your own peril,” Marjorie says. “Honestly, it’s not pretty.”

I borrow a six-pack of Yuengling from the conference room and call in an order to William Poll. I take a cab over to Lexington Avenue to pick up my little handmade crustless sandwiches on my way to Marjorie’s.

When she opens the door, Malcolm is screaming. There are three strollers in the entryway. A swing. A bassinet. Tons of baby gear everywhere.

“I’m really sorry; I thought you were exaggerating,” I say. “He really doesn’t stop crying, does he?”

“No. Well, yes, occasionally. But the two baby nurses who didn’t commit larceny said they’d never seen colic like this. Then they quit,” Marjorie says.

“I can watch him for a while; do you want to take a shower?” I ask.

“That bad?” Marjorie says.

“No. I just thought you could use a break,” I say. “It must be so hard to leave him,” I say.

“Not really. I take out the garbage just to get some ‘me’ time,” Marjorie says. “I never feel guilty. I envy these mothers who feel this sense of guilt.”

Marjorie says “these” as if referring to two or three mothers, or characters from fiction, but not real life.

“As soon as I find a baby nurse who won’t quit, I’m going to a spa in Napa for five days. Alone,” Marjorie says.

I just assumed every mother knows how to take care of her own child better than any stranger ever could. And within seconds, I realize how absurd that thought is.

“I’d kind of like to hold him,” I say.

“He’s yours, take him,” Marjorie says.

I rock him. I dance with him. I stand still with him. I try a pacifier. I try a bottle. I try music. I change his diaper. Still, he screams. I remember reading somewhere that babies like the sound of a vacuum cleaner because it replicates the noise they hear while in the uterus. Imagine sleeping next to a vacuum cleaner for forty weeks?

I buckle Malcolm into his swing. I turn it on. He screams. I start looking in closets for the vacuum cleaner. I find one cabinet that is devoted to Tupperware. The real stuff, not the cheapo knock-off Tupperware. No lid is attached to its bowl. Things are tossed about willy-nilly, which must serve as a huge deterrent from ever even opening that cabinet and enjoying such wonderfully overpriced containers. I can’t leave the kitchen without first organizing that cabinet. Who wants a plastic waterfall spilling out onto her kitchen floor? It’s not lost on me that I’m morphing into my mother. I can’t control it. The scary thing is I don’t even want to control it! I enjoy organizing. I see what the payoff is! Serenity! I complete the task and then remember I was looking for a vacuum. The best I can find is a Dust Buster. I race back to the living room.

Marjorie is standing in the doorway with a towel on her head. She’s wearing a robe.

“What happened?” Marjorie says.

“Nothing. I heard that vacuum cleaners work,” I say. “Is this all you have? A Dust Buster?”

“I don’t know. Cleaning is not my department. How’d you get him to sleep?” Marjorie says. “He’s cried every time we’ve put him in that swing.”

“He screamed when I put him in it, too. I just needed a safe place to put him while I looked for the vacuum,” I say.

He’s sound asleep. I didn’t even have a chance to turn on the Dust Buster.

“Maybe he’s exhausted from the crying,” I say. “What did the doctor say?”

“He said, ‘Some babies just cry a lot and yours is one of them.’”

“Find a new doctor,” I say.

What really shocks me is that people are still having babies. It just seems so strangely optimistic.

I unwrap the sandwiches and put them on plates. I make a salad. I open two beers. We sit on the couch, instead of at the table. Mainly because the table has become a diaper-changing station, where piles of unfolded laundry form soft sculptures.

“I’m not sold on his name. Little Malcolm. Maybe he isn’t, either. Maybe that’s the problem. Maybe it’s all a protest over his name.” Marjorie turns to look at him, as if he were a car, or a pair of shoes she was contemplating returning.

“It’s a little late for that, isn’t it?” I say.

“I was just being lazy when I named him,” Marjorie says.

“Oh, don’t beat yourself up over it. You only had nine months to think of a name, which he’ll only have forever!” I say.

“I thought it might charm Big Malcolm. You know, he wasn’t exactly fired up for a baby, so I thought naming him Little Malcolm might help,” Marjorie says.

“First off, I hope that ‘big’ was added only after the baby was born,” I say. “Are you afraid that Little Mal will feel too much pressure to live up to the name?”

“You’re forgetting who the original is,” Marjorie says. “If he can drink a few scotches and still toss his underpants in the general direction of the hamper, he’ll outshine his namesake.”

It’s eight-thirty. She looks tired.

“It’s time for me to go,” I say.

“Okay,” says Marjorie.

“Call me if you need anything,” I say.

“Okay, thanks for everything, especially the beer. And for telling me to take a shower,” Marjorie says. “How’s Mom?”

“Good,” I say.

“Is

it weird having Dad around?” Marjorie asks.

“Not as weird as I would have guessed,” I say.

“Why do you stay involved with these people?” Marjorie asks.

It’s as if I’m only supposed to ever have one parent. So the moment my mother becomes ill, my father grows remorseful for a lifetime of foolishness, and he tries to make up for two and a half decades of absent parenting. And I’m more than happy to let him try.

Slob Baby

UNTIL MY MOTHER got cancer, I didn’t know a lot about my father. I certainly had no idea what a gigantic weenie he was. He can be truly infantile.

We are in a cab headed to work.

“Driver, stop!” Dad says.

“What is it?” I ask.

“The plants. We need to go back,” Dad says. “I water the plants on Wednesday. I forgot. Wednesday can hardly continue without the plants being watered.”

It’s no joke. To his thinking, if the plants didn’t get watered, Wednesday would have to be on hold. I get it. I had to organize Marjorie’s Tupperware before I could leave the kitchen—but I thought I’d gotten that trait from my mom. Why couldn’t I have inherited a love of opera? Or something else that at least passes as a respectable hobby.

I look around his place while he takes the world’s tiniest watering can and fills it. He waters one plant, and then needs to go back to the kitchen for a refill.

“If you got a larger watering can, you could do this in a fraction of the time,” I say.

“I’m in no rush,” Dad says. “Besides, this watering can is perfectly fine. There is nothing wrong with this watering can.”

“Except that it’s too small for the job,” I say. “Maybe you had fewer plants when you bought it.”

“It’s the perfect watering can,” Dad says.

I look in his bedroom. There is a wet towel on his bed. In his bathroom, there is a wet towel on the floor. I pick them up and hang them over his shower door.

He continues watering plants. His zipper is unzipped. In the kitchen there is an empty box of Popsicles in the trash can.

“What did you eat for breakfast?” I ask.

“Popsicles,” Dad says.

“How many?” I ask.

“I don’t know, four or five, why?” Dad says.

“Your tongue is blue. I noticed it in the cab. But it’s blue every day. I always thought it was your mouthwash. Do you eat Popsicles for breakfast every day?” I ask.

“I’m a bachelor,” Dad says.

“Is that a yes or a no?” I ask.

“What if I do?” Dad says.

“Just a question, really,” I say. “Do whatever you want. But at least zip your fly.”

He’s the worst kind of slob baby I’ve ever seen.

I’m not sure what I expected. Having never lived with a man, and not having a father for most of my life, men are a bit of a mystery to me. He’s a bachelor? I admire him for that—for confusing being alone with being a bachelor. In my opinion, if you’re playing tricks on yourself, this is one worth playing. It’s for the greater good.

I look into the kitchen. He’s standing there in front of an open cabinet. There are a gaggle of pill bottles in front of him. He uses one hand to feed pills into his mouth, and the other to swill water. He alternates this motion at record speed. He fires pill after pill into his mouth.

We didn’t come back to his place because he forgot to water plants. That part of this equation is reassuring. But it’s hard not to be unsettled after seeing his colorful eye-popping collection of tablets, pills, and capsules.

Raw Meat

WE MEET AT BERGDORF’S for deviled eggs and iced tea.

“I feel like a complete ass; I told my therapist I had a dream we had sex,” I say. “Do you think I should have told him that?”

“Hell no, that’s like throwing raw meat to a wild animal,” Marjorie says. She thinks about it for a minute or two. “Were you telling the truth? Did you really have a dream about jumping him? Or were you flattering him so he’d refill your Xanax?”

“Right. I made it up, like I do with all the stuff I tell my therapist,” I say.

“I’m still drunk from last night,” Marjorie says. She can’t stop laughing. “What does he look like? Is he cute?” More laughing. “Should I be seeing him, too? I got high last night; I still feel like I’m high.”

“You still get high?” I ask.

For a time, her single greatest skill was being able to convert any household item into a marijuana pipe. A carrot, a soda can, a cardboard paper towel roll…It was like watching a true origami artist having a fit of genius. She was fast, creative, and the pipe always worked.

Once, when we were both on summer break from college, we went to East Hampton for a weekend. She read a self-improvement book from cover to cover while I drove. Later, I opened the book and saw that the only heavily underlined chapter was the one called “How to Come Across 100 Percent Authentic to Everyone You Meet.”

Marjorie takes out a pack of Marlboro Lights and some matches. She lights a cigarette. She decided long ago to ignore the whole ban on public smoking thing.

“I thought you quit when you got pregnant,” I say.

“I did,” Marjorie says, still puffing. “But I’m not pregnant anymore. You’re going to be proud of me. I fired Nevin and Dory. No life coach, no food coach. And I cut the nanny back to part-time. I’m saving a lot of money, and I have no time to shop. It’s working out okay so far.”

The waiter taps Marjorie on the shoulder. He’s going to tell her to put her cigarette out. It’s going to get nasty. He’s going to have to pry the carcinogen from her hand.

“We have a seat in the kitchen for you if you’d like to finish your cigarette there,” the waiter says.

The world bends in her direction. Every day, it bends and twists to accommodate her. The topography molds, like wet clay, to hug her.

“Okay,” Marjorie says. “Be right back.”

I sit at the table finishing my iced tea. There are deviled egg carcasses still on the plate. I’m staring until the distance comes into focus. I see Sam, having lunch with a woman. Adults. They are having lunch and a glass of wine. I pretend I don’t see him. I reorganize things in my wallet. I resist the urge to look his way again. But I can feel the pull of him. Eventually, I turn to steal another look, and he’s gone.

Unanswered Letters

I LIE ON THE COUCH at home with a legal pad. I draw around the edges of the paper, too afraid to commit word to paper. I can’t shake the image of Sam on the opposite side of the restaurant. Sam is as close to me and as far from me as my father used to be. I thought it had to be that way. It never occurred to me before that you could learn to move closer, even this late in life. I thought mothers were the ones who were responsible for teaching us how to love.

Dear Sam,

There is some freedom in writing a letter you know no one will answer. Some torture and regret, too, of course.

Just as I think I’m pushing myself (theoretically) forward, I catch a glimpse of you out in the real world. In other words, I saw you today at Bergdorf’s having lunch.

I pretended I didn’t see you for about two minutes. I busied myself by tossing out old receipts and such from my wallet. When I turned around again you were gone.

My mother is recovering. I’m getting to know my father. There are days I feel lucky to be learning things about relationships that I should have learned when I was younger. And then there are mornings I wake up and get dressed and for several seconds I think I’m headed to my old job, and will be seeing you. When reality hits it always hurts.

You looked good and it was nice to see you. The wallet is organized now. Next time I’ll say hello.

xo, Emily

Café Habana

I’M IN MY CHAIR at work, enjoying my lumbar support. It’s a towel that I’ve rolled into a makeshift back-relief apparatus. Necessity is not the mother of invention. Boredom is.

I call my mom.

> “I’m in for the night,” she says.

“You sound exhausted. Are you okay?” I ask. It’s only six o’clock.

“Just relaxing,” Mom says.

“Okay, do you want me to bring dinner over to you?” I ask.

Her response is short and sweet, and in a whisper: “Honey, I’m not alone. Can I call you tomorrow?”

I try to stop myself, but an image of her tangled up on the davenport with Phil springs to mind.

“Good for you, Mom,” I say. “Call you tomorrow.”

“Okay, but not too early,” Mom says.

Oh! I didn’t need that much information. Will walks by the reception area.

“How are things?” Will says.

“Better than I thought,” I say.

“Glad to hear it,” Will says. “Your mom doing okay?”

“I think she has a date tonight,” I say.

“Not a bad idea. How about Café Habana?” Will says.

“Oh,” I say, thinking it might be nice to get away from work, home, and transient thoughts about Sam. “Sure. There’s always room for Cuban corn.”

Things start out nicely enough. The corn is good. But the tide shifts when Will’s one or two beers turn into nine! That’s 120 ounces of liquid! How is the human body supposed to cope?

The evening ends with my lifting Will’s youthful head up from the table and asking him if he knows his own address. I put his bike into the trunk of a cab, and walk him up three flights of stairs to his apartment.

At least I no longer have to wrestle with the question of whether I’m judging him unfairly due to his youth.

Cold Drink

WE’RE BY THE WATERCOOLER. His eyes are bloodshot.

“What did you think about last night?” Will says.

“So you remembered we went out last night?” I ask. “What did you think about last night?”

“What I remember of it was stellar!” Will says. “Sorry for getting…drunk.”

Ask Again Later

Ask Again Later