- Home

- Jill A. Davis

Ask Again Later Page 11

Ask Again Later Read online

Page 11

“Like who?” Mom says.

“Dad,” I say. It’s the first time I’ve called him Dad.

“You’re nothing like him,” Mom says.

“I didn’t say I was like him, I said I was surprised that I like him,” I say.

“He can be very charming,” Mom says.

Charming is code for unfaithful. My mother is still very much a lady. Ladies do not discuss men who stray.

“I wonder if it was difficult for him, just leaving home like that and never really knowing us afterward,” I say. “It must have been.”

“You’re too empathetic, “Mom says. “You can always imagine the other side, and so you can’t quite get mad at anyone, can you? I don’t think that’s healthy.”

It’s the truest thing she’s ever said to me.

“We’re spending too much time together, Mom; it’s starting to drive me a little crazy,” I say.

“Yes, I sensed that,” Mom says. “But I so enjoy the company.”

One Bad Apple

MY SANITY SAVIOR for the moment arrives in the form of a potential client. Or so I think. My guess is that he’s in his fifties. He keeps calling saying he needs to talk to a lawyer “pronto.” When I explain he needs an appointment, he hangs up. Then I imagine he walks around his hovel of an apartment wringing his hands, drinking beer, then dialing again. In order to get a different result, you need to have a different response. So I do. This time.

“Civil or criminal?” I ask.

“Criminal,” he says.

“Violent or nonviolent,” I ask.

“They say violent, but I was just tryin’ to help,” he says.

“Well, we have many qualified attorneys; unfortunately, they’re all busy. So you can make an appointment and come in next week,” I say.

“It can’t wait,” he says.

He also sounds like he can’t pay.

“Can I just explain it to you?” he says.

“I’ve got a few minutes,” I say.

“Long story short,” he says. “I’m volunteering at this suicide hotline and this guy calls and he’s miserable and he says he’s going to kill himself. He starts telling me about his awful life—no job, no wife, house burnt down, car was stolen, twice. No auto insurance. He has Lyme disease. No health insurance. He’s allergic to every food imaginable. He’s manic-depressive. Nothing about his life is easy. So he calls three days in a row saying he’s going to kill himself because he’s so miserable. I try an’ talk him out of it. Then the fourth day he calls, and I’m like, Look, buddy, meet me at Pier fifty-seven tonight at six P.M. I get there. I push ’im in. I jump in after ’im. I hold ’im under water for forty seconds. No dice. I’m tellin’ ya, he had gills or something. I hold ’im under a minute. He’s kickin’ like a mother. Well, turns out the son of bitch didn’t really want to die after all, and now he’s pressing charges, sayin’ I tried to kill ’im.”

“You tried to drown him?” I say.

“Tried my best,” he says.

“Was this protocol recommended in the volunteer handbook?” I ask.

“No, but at some point it’s put up or shut up,” he says.

“Acquiring that level of misguided conviction is almost artful,” I say. “It’s borderline impressive. Now, you’d been volunteering for the hotline how long?” I ask.

“A month,” he says.

“This was your first attempted murder?” I ask.

“Are they gonna ask that?” he asks.

“Who?” I ask.

“The cops,” he says.

“I don’t know. I was just curious,” I say. “Listen, you’re not volunteering anymore, are you?”

“’Course I am, I’m not letting one bad apple spoil it for the rest,” he says.

“You are the bad apple,” I say.

There is a pause. “That’s tricky; are the cops going to say tricky things like that?” he asks.

“I don’t know, I’m a receptionist. I’m not a cop,” I say.

He hangs up.

Lunch Break

AT LUNCHTIME, I use my minutes wisely. I have forty of them. The elevator up and down eats up four minutes. Just thirty-six minutes left. I go to the bank. I buy a bottle of water. I have twenty-six minutes left. I’ve never been more aware of how much time matters.

I line up for a salad at a place that offers sixty salad toppings. I get overzealous, due to the mountain of choices. I get hard-boiled eggs, mushrooms, shredded cheese, chickpeas, avocado, tofu, green peas, and bacon all heaped onto lettuce then shaken together with their house dressing. It was fun making it. But once it’s all combined, I have no desire to eat it. I pay for it and walk down Fifth Avenue.

Fifteen minutes to go. I sit on the steps of the New York Public Library and try to catch some spring sunshine. I open the salad and start to eat. I see a pea on my fork. The size of a pea…I think about cancer and feel nauseous. I put the salad back in the bag. So I watch people. There are people kissing. People talking to themselves. People spitting.

I see my father and a woman eating hot dogs next to the hot dog and gyro stand. They are fifteen yards away from me. When they are finished eating, my father squeezes the woman’s shoulder. They hug. Then they walk in separate directions. He looks happy, but his steps seem heavy, in slow motion. He’s getting older. The opportunity to know my father as a younger person is gone.

I stand up. Six minutes to get back to work. I think about my father hugging the woman just moments ago. He’s making much better use of his lunchtime than I am. He gives me an idea.

Postcard

I BUY A POSTCARD and stamp in the library gift shop. I take a pen out of my purse and, in large type, I write:

Dear S.,

There is so much to say. Unfortunately, it won’t all fit on this postcard.

E.

I surprise myself by mailing it.

Wacky Sock Day

TODAY IS WACKY Sock Day. I’m wearing a pair of rainbow-colored knee-highs. My father is wearing socks with crossword puzzles on them. This is depressing. It indicates he does pay some attention to detail…yet for two decades he managed not to remember he had a family.

“I look forward to this day all year long,” says Wendy. “It lightens the mood and gives everyone a chance to express their creativity.” Her socks feature different colored cats, all playing with balls of yarn.

“Since when is buying a pair of socks that aren’t just black or blue considered to be the creative process?” I ask.

“Don’t be a spoilsport!” Wendy says. “I look for fun socks every time I’m in a clothing store. It wasn’t a coincidence that I found these. I hunted for these. I saved them for today.”

“Maybe you all could sign up for a pottery class or something—so we can put an end to this collective humiliation. I’m no spoilsport; I wore the socks, didn’t I?” I say. “People were hissing at me on Fifth Avenue when I was coming into the building. I don’t want to start my day that way.”

“Rookie mistake,” says Wendy. “You put the socks on when you get to work. You don’t wear them to work. Think of riding the subway and imagine the person most likely to get mugged—it would be the person with the cute socks, right? They make a person look so innocent. Like a victim. It’s okay, you didn’t know. Well, I’m off to organize the trash bags in the kitchen. Someone keeps mixing the six-gallon mini-bags in with the thirty-two-gallon kitchen-size bags.”

Will steps off the elevator. There’s something appealing about his shaggy-dog, I-could-live-on-$12-a-week look. He’s wearing navy socks with pinpoint white dots. Ah, wacky for him. He is a monochromatic sock guy. Navy. Black. Khaki. No stripes. No disruptive variations on the theme. I buzz him in, quickly, because if I leave him out by the elevators too long someone else might grab him before I decide if I want to or not.

“That’s a great idea,” I say, staring at his ankles.

“What?” Will says.

“Subjective wackiness,” I say. I imagine us much late

r, in year two of our unlikely odd-couple marriage. I will learn that he has a sock “theory.” He buys them in bulk, so when they get lost or mismatched, well, they don’t. When you have ten pairs of the same socks, you don’t spend much time sorting. The day he tells me this—confides really—I will start the “Will’s Economy of Time File.” Throughout the happy course of our marriage, I will add gems here and there. We will create oddball traditions of our own. And then it hits me: I am imagining a future. I never do that.

“Are you sticking around tonight?” Will asks.

“For what?” I say.

“No one told you? It happens only once every one hundred twelve years or something, when Pluto’s moons are all in line. Wacky Sock Day coincides with Thirsty Thursday,” Will says.

“Pluto has only one moon,” I say. “What’s Thirsty Thursday?”

“Beers in the conference room after hours,” Will says. “Why do you know that Pluto has one moon?”

“I have a lot of time to read,” I say. “Did you know that Mercury and Venus have no moons? Jupiter has sixty-two.”

“A two-class solar system,” Will says.

“Not really, Earth has one, and you don’t see people losing any sleep over it,” I say. “One seems like plenty. Maybe sixty-two are too many. Maybe a lot isn’t a good thing in the case of moons. How special would a full moon be if you had a chance to see sixty-two of them?” Stop talking! For the love of God, Emily, just stop talking!

“You’ve given this some thought, haven’t you?” Will says.

“I guess I have,” I say.

I’m the one who will eventually get to leave. I need to remember that. But for now, the invitation is appealing. Something tells me my predecessor Esther never missed a Thirsty Thursday.

Toward the end of the day, there is a palpable energy in the air. A quiet thrill is waiting to be unleashed. It is five fifty-five…Wendy steps off the elevator. I buzz her in. She carefully maneuvers a pushcart. A chariot. She’s the hero who gets to roll in all of that wonderful beer. No expense has been spared. Winter ales. Light beer. Japanese beer. Mexican beer. It’s an eye-popping tower of chilled hops.

No great decorative preparations are made on Thirsty Thursday. All the money is in “product.” This surprises me.

“No decorations?” I say to Wendy.

“Oh, good idea! You be in charge of those for next month,” Wendy says.

“I’m not sure I’ll be here next month,” I say. “Besides, I thought it seemed like something you’d enjoy doing.”

“I’m really more of an idea person,” Wendy says.

“Okay,” I say.

My father walks over and hands me a beer.

“It’s a twist top,” Dad says, sounding jubilant that someone thought to invent such a convenient way to get a bottle of beer opened.

“I see that,” I say. “Thanks.”

“I just knew you’d enjoy working here,” Dad says. “It’s a bevy of activity. All thanks to Wendy.”

She smiles from across the room. Wendy is in love with my dad.

“How long has Wendy been working here?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” Dad says. “A few years. Quite a while, actually.”

“A few? It’s been fifteen years,” I say. “She told me today.”

“Has it really been that long?” Dad says.

“Time flies,” I say.

“Yes, it does, doesn’t it?” Dad says. He takes a sip of his beer.

Herman from billing wants to know how much people will pay him to drink six beers in under ten minutes. People start throwing money on the table. I think Herman might do this at home, for free, so I don’t put any money on the table. It’s a diversion. Herman is looking for free beer, fast. Not money. People are always more strategic than you expect them to be.

I sit down in a swivel chair. I peel the label off the beer bottle. It’s an undocumented symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder. I think about crafting a letter to a psychological journal and letting them know about the label-peeling thing. I decide I’ll write it first thing tomorrow. I’ll put it on the firm’s letterhead so it might be received with more excitement and regard.

“Is this seat taken?” Will asks.

“No,” I say.

“A label peeler, huh?” Will asks.

I nod.

“In college that meant a girl was easy,” Will says.

Mental note to self: Skip writing letter to psychological journal.

Just then another employee stands on the table and says she wants to know how much people will pay for Herman to drink two beers at once. Herman takes his newly earned cash, sticks it in his pocket, and climbs on to the table.

“Two beers at once? I’ll do it for free,” Herman says.

Of course he will! These people have it right, I suppose. They are at least inventing ways to collide into each other, get closer.

Labor

GROWING UP, OUR KITCHEN had ecru-colored walls, eggshell finish, with some mica powder rubbed into it. It looked like fairy dust. We weren’t allowed to touch the walls.

Marjorie used to walk into our kitchen and touch the walls, while asking my mother a seemingly innocent question. It drove my mother crazy. That’s the difference between Marjorie and me. She’d touch the walls to make my mother angry. I went out of my way to do things perfectly, because my mother was already angry with me for being too much like my father.

“Please don’t do that, Marjorie!” Mom would say.

“Sorry,” Marjorie would say, smiling. She’d touch the wall again.

“Damnit, Marjorie!” my mother would say. “Stop touching the walls with those filthy hands!”

It’s three-thirty in the morning. My mother knocks on my door. She hands me the phone. When she calls in the middle of the night—in labor—Marjorie is still touching the walls. At least that’s how my mother sees it.

“This has got to stop. Please tell your sister not to call after nine P.M.,” Mom says.

“Why don’t you tell her!” I ask.

“You better get dressed. She’s in labor,” Mom says.

“Maybe that’s why she’s calling in the middle of the night, Mom! Marjorie?” I say, taking the phone from Mom’s outstretched hand. “What do you want me to do?”

“Malcolm’s in the air. Literally. He’s coming home from London. I’ll take a cab to Mom’s place; I’ll be there in a few minutes. Can you wait out front and come with me? Malcom’s—ohhhhh…”

On The Passionate & the Youthful, they deliver babies everywhere except in a delivery room. So I know babies can be born in cabs, in elevators, in locker rooms, in restaurants, and at major sporting events. In each case, someone “coaches” the mother-to-be. Coaching mainly involves reminding the person to breathe. Then offering lots of congratulations when the mother-to-be does breathe.

“Marjorie, you can do this. Breathe,” I say.

I hear her breathing on the other end. I immediately like coaching and find it very rewarding, even though you say very obvious things that the other person would be doing anyway. Somehow, I still feel like I’m doing a good job and that I am, at the moment, irreplaceable. I feel needed. I like that.

“You’re doing great,” I say. “I’ll be downstairs in five minutes; remember your suitcase. I know you bought new luggage for this, so be sure to bring it with you!”

“Ohhh…”

“Bring a camera, too,” I say.

“Oh, right, I have to find the camera,” Marjorie says. “See you in a few minutes.”

I brush my teeth and throw on jeans and a sweater. I grab my purse.

“Take a book,” Mom yells from her bedroom. “It’s a lot of hurry up and wait at that hospital.”

“Thanks,” I say. “Do you want to come along?”

“No, but if you get tired, I can take over,” Mom says. “Call me.”

Baby

LITTLE MALCOLM HAS the most perfect little round head and big blue eyes. The tiniest fee

t and fingers. They seem too tiny to function. His lips and skin are red, and his hair is jet black. He looks like a skinny wet kitten. I can’t help but stare in amazement at the only seven pounds that could ever truly change Marjorie’s world.

They weigh him and measure him, and roll his feet on an ink pad. What a clumsy introduction to the world. I get to hold him while Marjorie is being taken care of. He looks at me. He’s studying me. Staring at my enlarged pores. I turn my head. He keeps looking, the unrelenting observer.

I whisper in his ear, confiding: “I’ve tried facials, I’ve tried minimizers. Nothing works!” He smiles. He knows stuff. He burps, and in that burp, I’m convinced, was a message: Try alpha hydroxy.

“He’s so sweet. I’ll baby-sit sometime if you’re in a pinch,” I say.

“Okay,” Marjorie says. Then, to the doctor, “It feels like World War II down there…is that the way it’s supposed to feel?”

“Well, yes, but you shouldn’t be feeling it,” the doctor says. She opens the floodgates on Marjorie’s IV. Less than a minute later Marjorie gives a thumbs-up sign, and falls asleep.

Big Malcolm arrives, jet-lagged, just in time to accompany Little Malcolm to his first bath. Once the baby has been whisked away, Marjorie is moved to a new room.

She insists on changing into some expensive Egyptian cotton pajamas. So Joanie! I brush her hair.

“I want to kiss that epidural guy,” Marjorie says.

“You always did go for Mr. Popular,” I say.

“Only because I’m not thoughtful enough to find a diamond in the rough,” Marjorie says. “What can I say? I’m not a worker bee.”

“You just spent fifteen hours in labor,” I say. “And you have the energy to imagine hypothetically kissing the anesthesiologist. You work much harder than you give yourself credit for.”

“Then why can’t I be bothered to pick out my own clothing?” Marjorie asks.

“I don’t know. Because stores are too big now. It takes forever to shop,” I say. “Tell me you’re not hiring a personal shopper for the baby’s clothing, though.”

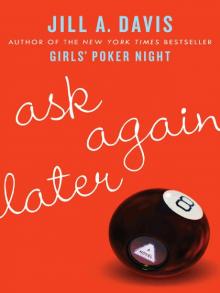

Ask Again Later

Ask Again Later